I was happy to see the snow coming down last Sunday as I let the dogs out. They bolted down the porch stairs, ripping around the backyard like furry maniacs, kicking up frozen plumes behind them before skidding back up the porch stairs at full speed and staring at me through the glass to let them back in. I toweled them off, the room filling with the smell of wet, happy dogs.

I knew the snow would stick around only for a few days, so I made the most of it, entertaining Mike and Facebook friends with a quick snow angel on the porch. The driveway is my least favorite part of the winter, though, with slick tracks forming on the pavement from our cars moving in and out of the garage. Several years ago, I earned my first set of stitches after taking a tumble on an icy patch with a bag full of recycling in my hands. Beyond the stitches, it was only my pride that was hurt. How had I taken such a bad fall on ice in Arizona?

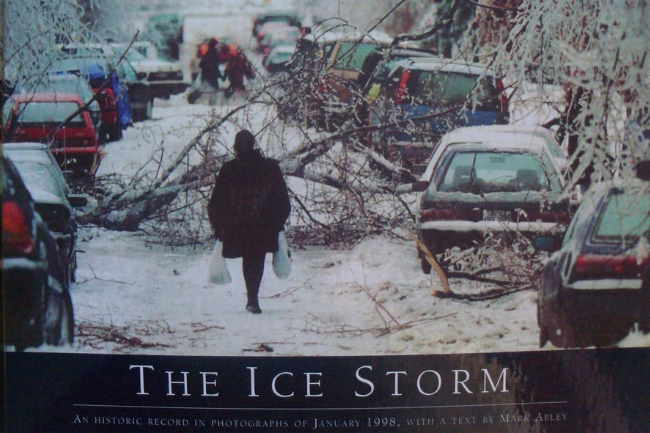

But of all the snow adventures we’ve had in our lifetimes, the one that sticks with me most happened in January 1998 when we were living in a tiny town near Ottawa, Ontario. It was an ice storm impressive enough to have its own Wikipedia page. It carved an enormous path of destruction around northern New York and eastern Canada, knocking out power for weeks in some areas, including our house.

It started small, with freezing rain that bent the small trees near our house. We lived in the middle of a pine forest, which had been planted in neatly spaced rows. As the rain continued, the power went out. All through the night, we heard what sounded like gunshots, but it was the tops of the pines snapping under the weight of the ice or tipping over like dominoes to form giant circles of downed trees. The next morning, our yard was full of fallen treetops. Miraculously, only one had hit the roof and made a small hole.

It took a few days for us to clear our driveway and see the damage all around us. The power lines were dangling and transmission towers, usually so imposing, were crumpled into heaps as far as the eye could see. The next three weeks were full of challenges, but what I remember most was how tired I was just trying to stay warm and fed while living in a house that wasn’t built to work without electricity. We had baseboard heaters and a waterbed, neither of which was useful after the power went out. Luckily, we had a wood stove in the basement that provided some heat. We slept on couch cushions, cooked macaroni and cheese on the wood stove, and tried to make the best of things.

Crews from all over the U.S. and Canada worked hard to get the lines back up, even temporarily. We’d drive past the local motel on the way to the grocery store and see license plates from everywhere. We were so grateful people were willing to show up, in the coldest month of the year, to help us.

The other day, one of our hospice patients mentioned growing up in Detroit and playing hockey with Canadians. I told him I’d lived in Ottawa for a few years. He said he’d spent some time in Canada working as a lineman during a really bad ice storm. “The big ice storm of 1998?” I asked and he nodded. “No way,” I said. “We lived through that storm. I have a book on it.”

The next 15 minutes flew by as we shared a few of our best stories from that time. He told me how hard it was for the crew to find a bottle of whiskey in Quebec, where they were stationed in old military barracks. That he was still in touch with some of the guys from that storm, and what a kick they’d get out of hearing he’d met someone who lived through it. I promised I’d run home that afternoon and get the book to show him. When I came back with it, it felt like handing over a long-lost treasure. He flipped through a few of the pages and we commented on the crazy amount of ice damage in the photos. I left it with him to enjoy while I went back to work. I didn’t get a chance to talk to him again – he passed away a few days later. When I got the book back, one of the pages had a bookmark in it. It was a photo of a lineman working on the downed power lines. I’d like to think it was him.

Prescott-area resident Kelly Paradis is a community liaison for Good Samaritan Home Health, Hospice & Marley House. She loves listening to and writing stories about life.